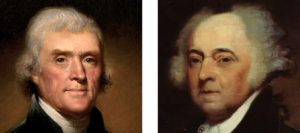

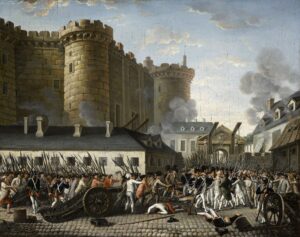

Important men and women driven by profound, ground-breaking ideas with everything at stake in a crucial period of American history; two paths, three countries, two key men, allies and enemies; cooperation, conflict, danger, sacrifice, courage, love, betrayal, resentment, forgiveness, greatness.

An essential story of American history told for a new generation.

History is a “distant mirror” as Barbara Tuchman famously said about the 14th century. We need to look in the mirror – and not avert our eyes.

♦

♦